by Miceál O’Hurley

DUBLIN — One of the biproducts of Russia’s 8-year long war on Ukraine is a direct threat to the right of freedom of navigation on the Black and Azov Seas. While the Azov Sea is often referred to as the ‘Internal Sea’ of Ukraine and Russia, the Black Sea is bordered by Georgia, Türkiye, Romania and Bulgaria. The threat to international freedom of navigation isn’t alone posed by the prospects of Russia extending its occupation of Ukraine along the entirety of its coastline. Given Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2021 essay in which he made abundantly clear his desire to rebuild what had been the Russian and Soviet empires concerns that the Russian Federation would attempt to extend their occupations in Georgia to the entirety of the country and subjugate the rest of Moldova aren’t entirely misplaced. Such events would put pressure on Romania and Bulgaria to waver in their commitment to the EU and the West and could serve to destabilise them, and the EU, in much the way Hungary currently does.

From the beginning in 2014 when Russia began its combat operations against Ukraine their desire to cut-off Kyiv from its vital sea access, ports and shipping has been a cardinal objective. Today, with Russia having widened its combat operations against Ukraine, seizing key ports such as Mariupol and Odessa would help them complete their goal of denying Ukraine import/export operations by sea and strike a further blow to the country’s economic base. Moscow’s objective promises security and economic consequences that extend far beyond Ukraine and will impact regional if not world shipping. In June 2021, Russia famously fired warning shots at the HMS Defender, a Daring class air defense destroyer conducting freedom of navigation exercises in international waters on the Black Sea. Russia has proven it has no qualms about claiming any and all rights to shipping on the Black and Azov Seas despite lacking any legal authority in international law.

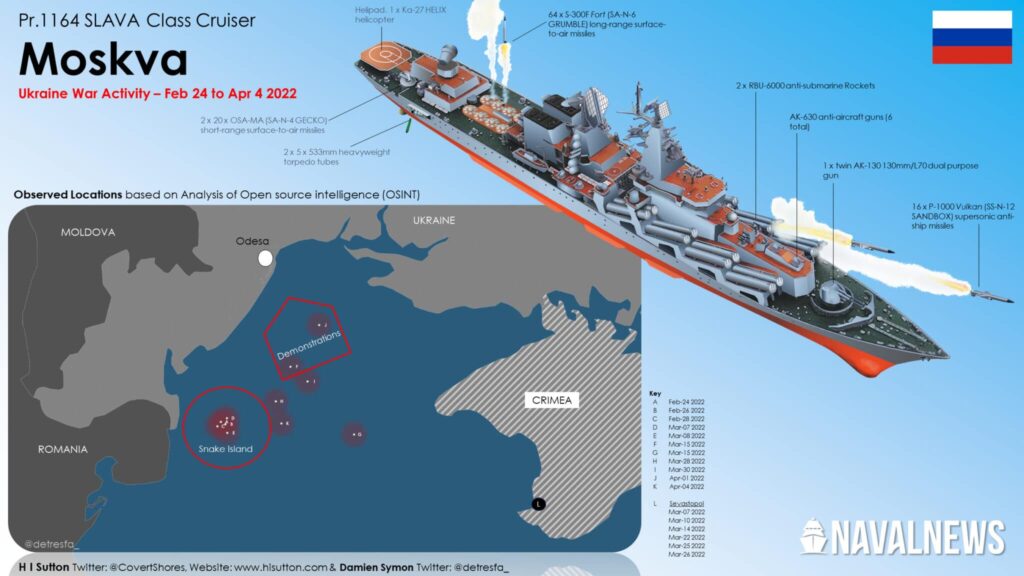

Beyond the threat to international shipping, the seizure of Crimea and key seaports such as Sevastopol in 2014 have had a deleterious impact on Ukraine’s Navy. Deprived of many of their vessels, the Ukrainian Navy numbers barely over 5,000 sailors. Its fleet has been reduced to mainly coastal patrols boats, including those supplied by the United States. Russia, by contrast, maintains a far superior Navy in terms of personnel, equipment, firepower and vessels. Even after the loss of their prized flagship Moskva and the missile frigate Admiral Makarov which Ukraine sunk in the past few weeks, the Russian Black Sea Fleet still numbers more than 40-warships and myriad support vessels. Provided it can make use of the Bosporus Straight and Türkiye does not exercise its prerogatives to inhibit passage under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Russia can draw on its fleets deployed around the globe at will to maintain superiority at sea.

Despite this gross imbalance of power, Ukraine’s Navy has ‘boxed above its weight’ since 24 February. From sinking vessels in port to the sending the pride of the Russian Navy, the flagship Moskva and the frigate Admiral Makarov to the bottom of the sea using Ukrainian designed, built and launched R-360 Neptune missiles, Ukraine’s Navy has performed far beyond anyone’s expectation. Indeed, the entirety of Ukraine’s Armed Forces have exceeded all Russian forecasts and that of Ukraine’s NATO and EU allies alike. Ukrainian Air Force, Army, Marines and Naval Infantry, as well as the Ukrainian Navy have combined to deal significant injuries to Russian Federation forces. At sea, since February, Ukraine has managed to sink the Saratov – an Alligator class landing craft; the Moskva – a Guided Missile Cruiser; 2-Raptor class patrol boats; a Serna class landing craft; and, the Admiral Makarov – a frigate. Several other Russian vessels have been observed retreating with fire and smoke after having been effectively engaged by the Ukrainian Navy. Moscow has ever reason to worry.

The sleek, sophisticated and lethal Neptune missiles have proven that even from land Ukrainian Forces can contest control of the sea. Using drones manufactured by neighbouring Türkiye, Ukraine sank 2-patrol boats of the Russian Navy only last week. These are not the only tools in the Ukrainian Navy’s arsenal. Great Britain has announced the scheduled delivery of hundreds of their highly effective Brimstone anti-ship missiles to beef-up Ukraine’s maritime defense capabilities. Coupled with Western intelligence, largely from the United States and Great Britain, the relatively tiny Ukrainian Navy is likely to continue to prove being the ‘Davey’ to Russia’s ‘Goliath’ for the foreseeable future.

Russia’s attempt to throttle Ukraine’s ability to actively exercise freedom of navigation in their own territorial and international waters has already landed Russia before the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). In successive orders in April and May of 2019, ITLOS ruled in favour of Ukraine who sought relief from the Russian Federation’s detention of 3-Ukraine ships and their crews. Russia complied with the Order by eventually returning the ships but did so having looted them of much of their equipment and rendering them largely unfit for service. Should Russia achieve its objective of taking Odesa and completing their land occupation of Ukraine’s seafront territory Russia would undoubtedly seek to annex these territories to claim exclusive rights to what are lawfully and internationally recognised Ukrainian land and waters. The West must prevent this at all cost.

On 2 May, the Ukrainian Ministry for Agriculture announced they were officially closing several key seaports. The Azov Sea ports of Mariupol, Berdiansk and Skadovsk and the Black Sea port of Kherson were closed “until the restoration of control,” the Ministry said in a statement. “The adoption of this measure is caused by the impossibility of servicing ships and passengers, carrying out cargo, transport and other related economic activities, ensuring the appropriate level of safety of navigation,” it said.

With Russia now in command and control of approximately 2/3rds of Ukraine’s coastal territory, and Mariupol holding-on by a thread, Russian occupational forces’ waterfront footprint is sizable and strategically advantageous. The seizure of Odessa would make their campaign complete. Cutting off Kyiv’s control of its Black and Azov Sea ports would also serve to effectively blockade the Dnieper River. The stakes are high for Ukraine. They are equally so for international interests and poise strategic consequences for an entire region.

Ukraine, widely dubbed the ‘Breadbasket to the World,’ has nearly a quarter of the world’s most fertile soil, known as Chernozem. My personal observations of planting throughout Ukraine last month coincides with the Ministry for Agriculture’s estimates that only between 30-50% of Ukraine’s planting will take place in 2022. Already the winter wheat requires pesticide applications to ensure a sufficiently high yield and planting of the summer crops is severely diminished. There are myriad reasons for this – all biproducts of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Diesel is in woefully short supply. Farm machinery has been significantly looted or damaged by Russians. Even routine spare parts are in critically short supply. Worse still is the labour shortage – farmers are serving on the front lines defend Ukraine from the Russian onslaught. As for operating cash, it is almost non-existent. Farmers are attempting to do their best with many small farms reverting to the plow and horse to plant. The Ministry for Agriculture has already been forced to direct farmers to plant non-export crops to help ensure Ukraine’s domestic food security.

The world is already starting to feel the effects of the forecasted shortfalls that is already resulting in global food scarcity. Domestically, Ukrainians whose grain made bread for the world now are at risk of standing in bread lines. According to David Beasley, Executive Director of the U.N.’s World Food Programme said, “Half of the wheat the WFP needs is stuck in Ukraine.” The agency has already cut back ration to the more than 115.5 million people around the globe who rely solely on the UN organisation for its work. Ireland is a proportionately significant contributor to the World Food Programme. In 2021, Minister of State for Overseas Development Colm Brophy, TD announced a 3-year strategic partnership with the World Food Programme amount to €75 million.

The consequences of the West allowing Ukraine’s most vital, remaining port, Odessa, to fall into Russian hands would prove staggering. Russian occupation of Odesa would significantly cut-off Ukraine’s access to global markets. It would assuredly render sustaining their economy and any eventual recovery extremely difficult. Russia’s gamble to take Odessa and complete its land-bridge to Moldova would also imperil Europe further. Moldova, which already suffers Russian occupation in its Transnistria region, is part of the ‘Three Amigos’ comprising Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova which are seeking expedited membership into the EU. Russia’s designs on Moldova are real, immediate and seeks to destabilise Europe and NATO even further. Already the default blockage of Ukraine’s most vital remaining seaport, Odesa, serves to sever the Ukrainian economy from global markets. Should Russian forces be able to stabilise their occupation of Mariupol, bring pressure to bear on Odesa by land and attack the port city with naval firepower from sea Ukraine and by proxy, international shipping would be further imperiled.

The need for the West to step-up its rapid equipping of heavy armour and advanced defensive weapons systems to Ukraine is becoming ever more paramount. While President Biden’s proposed $33 billion (USD) aid package for Ukraine does include some coastal-defense hardware it is hardly enough. Still, the likelihood that the package will be rapidly approved by the Congress was bolstered by Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s unannounced visit to Kyiv. Pelosi was accompanied by key members of the House leadership team including House Intelligence Committee Chair Adam Schiff and Foreign Affairs Committee Chair Gregory Meeks. During their visit, which followed by 1-week the visit of U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s, Pelosi was quoted as saying the 3-hours she spent with the “dazzling” Ukrainian President was “a remarkable master class of leadership.” She is clearly conveying the confidence of the U.S. Congress in Zelenskii. Ukraine enjoys significant bi-partisan support from both the Democrats and Republicans in the House and Senate.

Pelosi, who is 3rd in line to the Presidency behind Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris told Zelenskii, “Our commitment is to be there for you until the fight is done. We are on a frontier of freedom and your fight is a fight for everyone. Thank you for your fight for freedom.” Chairman Meeks even added to the view that America’s commitment to Ukraine was far from finished, “Nothing is going to decrease, everything is going to increase,” said Meeks. While the US President is responsible for foreign policy, the division of powers in the United States Government places the purse-strings in the hands of Congress. In many ways, Pelosi’s visit was a harbinger of increased and unceasing support from the U.S. as well as a virtual guarantee of fully-funding Biden’s $33 billion request for Ukraine without delay. Chairman Meeks’ statement forecasts a decisive shift in U.S. policy from helping Ukraine defend itself to one of focusing on Ukraine outright winning the war Russia began 8-years ago. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has already indicated the U.S. now believes it is in their interests to “Degrade Russia’s ability to wage war against its neighbours.”

For the immediate, given the scarcity of Ukrainian Navy vessels, it becomes incumbent upon the international community, and in its self-interest, to exercise its right of freedom of navigation in the vastly international waters of the Black Sea. Ukraine is certain to cooperate in bolstering this exercise by granting friendly access to its territorial waters and the country’s 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone. In the event the world community would cede these vital waters to the Russian Federation by default it would have an enduring and deleterious impact on world food security for years to come. Moreover, it would also further imperil the independence of Moldova and Georgia, two countries which Putin has already declared should be returned to Russia’s sphere of influence. In the event the Black Sea would be reduced to a predominantly 2-country coastline – assuming Bulgaria and Romania will come under increasing harassment and pressure to drift back within the Russian sphere of influence – the regional balance of power would pit Türkiye in an ever more precarious position between Europe and Russia.

Assisting Ukraine at this time with enhanced anti-ship and coastal defense weapons systems, accompanied by training, is the most assured way the West has in ensuring Ukraine not only survives Russia’s punishing and illegal warfare, replete with human rights violations and war crimes. Accompanied by robust exercises of freedom of navigation on the Black and Azov Seas the West has every interest, in terms of security, economics, food security and the rule of law in playing a more active role in the region’s waters at this moment in history.

___________________________________

The following information is published by the Ministry for Infrastructure of Ukraine (http://mtu.gov.ua), relying on information from SE Ukrainian Sea Ports Authority (http://www.uspa.gov.ua/en/), SE Ukrainian river ports Authority (http://www.arport.com.ua/), Ukrrichflot (http://ukrrichflot.ua/en/);

Ports Daily Loading/Discharging Capacity

No |

Port |

Port specialization |

Capacity (MT, in thousands) |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Berdnyanskiy |

Light vehicles, fruits, sugar, metal |

3 to 5 |

2 |

Mariupol |

Grain, metal, coal, construction materials, oil,other equipment, food and containers |

3 to 10 containers vessels, dry-cargo for coal |

3 |

Kerchensky |

Metal, glass, equipment, cotton, livestock,light vehicles, foodstuff, coal and containers |

3 to 810 for metals |

4 |

Odessa |

Metal, construction materials, equipment,grain, sugar, woods, food stuff, coal, chemicalsand containers |

5 to 55(draft up to 12.5 m) |

5 |

Ilychevks |

Grain, light vehicles, equipment, food stuff,cotton and containers |

5 to 50 |

6 |

Yuzhniy |

Liquid, chemicals, construction materials, coal |

up to 65 |

7 |

Nikolaev |

Grain, cement, woods, oil products, metaland containers |

up to 30 |

8 |

Kherson |

same as above |

up to 20 |

9 |

Bilhorod-Dnistrovsky |

Metal, cotton, grain, food stuff, woods, sand,single units and containers |

up to 5 |

10 |

Feodosia |

Metal, construction materials, oil products,woods, frozen goods, coal, and containers |

2.7 to 10 |

11 |

Izmail |

Grain, coal, construction materials, food stuff,woods and containers |

up to 5 |

12 |

Reni |

Oil products, single units |

N/A |

13 |

Oktyabrsk |

Metal, general cargo and containers |

up to 10 |

14 |

Yevpatoria |

Mineral-construction materials |

5 |

15 |

Sevastopol |

Mineral-construction, woods, oil products,metal, general cargo and containers |

2 to 40liquid 15dry-cargo 10 |

16 |

Dnenproburzhsky |

Syrup, acid goods, metal, cement, spare parts |

N/A |

17 |

Dnepropetrovsky River Port |

Grain, metal, light vehicles, construction materialsand containers |

3 to 5(draft 3.5 m) |

18 |

Zaporozhsky |

Metal, chemicals |

1 to 5 |