by David A. Andelman

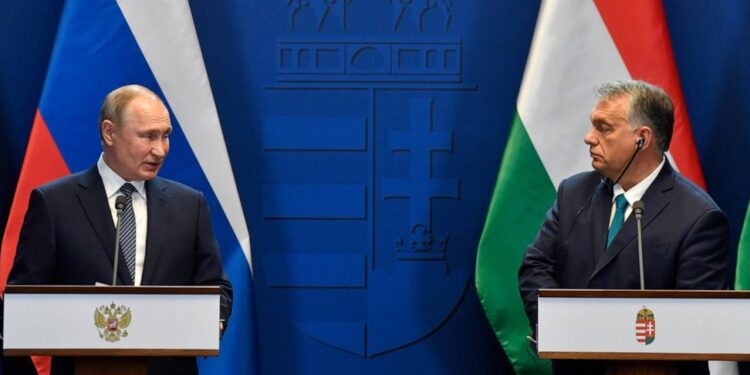

The looming presence of Vladimir Putin will be on the ballot in Hungary on Sunday. Not Putin himself, of course, but someone who all too often has looked, sounded, even acted very much like the Russian leader. This vote is a test not only for Hungary but for Europe itself, writ large. And now, just days before the nation goes to the polls to select a new leader or ratify an old one, it looks like Putin and his way of looking at the world may be winning.

For 12 years, Viktor Orban has held sway over a Hungary that he has pushed increasingly further from the West European mainstream that the country had occupied since it first joined the European Union along with seven of its former Warsaw Pact neighbors in 2004. For Hungary and the rest of Eastern Europe, it was a long and at times tortuous path from their days as Soviet satellites that ended when the Iron Curtain came down. Like its neighbors, for Hungary there was little question of their intention to become determinedly democratic, and capitalist—members of a European community they had long viewed with envy and deep desire through the prisms of an iron curtain. Then six years later, in Hungary, along came Orban.

His arrival in power represented the first wave in a tide of populist nationalism that began sweeping Europe before crossing the Atlantic even before the arrival of Donald Trump to cement this catastrophic course. Under Orban, a process began that would distance Hungary increasingly from the European mainstream.

From his earliest days in power, the hallmark of Orban’s reign has been an aversion to immigration. The rest of Europe banded together in 2015 to receive a wave of Middle Eastern immigrants at the moment Syria was coming apart at the hands of its dictator Bashar al-Assad and his supporter, Vladimir Putin. Germany alone under Angela Merkel welcomed a million. Orban chose instead in 2015 to build a wall preventing any from entering. The 12 feet tall chain-link fence, topped by rows of razor wire, built by contractors and some 900 soldiers at a cost of more than $100 million, stretches the length of the 100-mile border dividing Hungary from neighboring Serbia. It was as determined a statement as possible that Orban’s nation would be separating itself from the rest of Europe that was welcoming these Middle East refugees.

The fence was only the symbol of a broader philosophy of separation that only accelerated as Orban and his Fidesz party quickly cemented their hold over the nation’s society, politics, culture and most importantly its media. For there is more to Orban and his breed of nationalism than simply immigration. His fundamental purpose seemed to be rooted in distancing Hungary from much of what Western Europe represents. Simultaneously, Orban sought to reap the material benefits of membership in the European Union while distancing his nation from the democratic values it represents and embracing a Russian brand called Putinism—a self-referential, one-man rule of law that knows what was best for the nation no matter what people at home or abroad might believe.

“Putin and Orban belong to this autocratic, repressive, poor and corrupt world,” Orban’s leading election opponent, Peter Marki-Zay, mayor of the southern Hungarian town of Hodmezovasarhelm told New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg. “And we have to choose Europe, West, NATO, democracy, rule of law, freedom of the press, a very different world. The free world.”

At the beginning of the campaign, six long-feuding opposition parties joined together in a unique, at least in Hungarian terms, effort to send Orban and his Fidesz party to the back benches in parliament. It is now beginning to appear this effort will prove as futile as any previous attempts to remove the prime minister from power. The fact is all too many Hungarians have bought into his extreme vision of their nation and its place in Europe and the world.

Part of his appeal is his standing on the antitheses of the political platform of his opponents. The picture they paint is one that is domestic in the extreme—as Marki-Zay puts it “we want to give opportunity and not welfare checks to people.” The fear, of course, is that the promised lower taxes will be accompanied by a vastly reduced safety net that has protected Hungarians at all levels throughout the Orban rule.

So, what is the Fidesz program? It’s probably best expressed in what it does not represent, or how it suggests life may be like if Orban is sent packing: removal or vast reduction in state-guaranteed pensions, cancellation of the minimum wage, send their children to fight in Ukraine, even allowing sex-change operations for kindergarten students without parental permission. Moreover, this kind of information has been fed to voters in an uninterrupted stream on virtually all Hungarian media without a single opportunity for the opposition to present their case. Fidesz and its loyalists have quietly bought or subsumed all major Hungarian media—print, television, radio and online.

At the same time, the war in neighboring Ukraine has become more intense, sending at least 200,000 refugees pouring across one stretch of Hungary’s border that has not yet been fenced or barricaded.

So, the fear of changing horses in mid-stream to someone prepared to challenge rather than embrace Vladimir Putin becomes all the more difficult for many Hungarians who have long coveted the reassurance of the status quo. In short, the devil they know is far better than an angel they do not fully trust to look after them and keep them and their families secure.

Orban himself has also been making it easier for voters to continue to accept his leadership even in these parlous times. He’s made no secret of being warmly received by Putin in the Kremlin just three day before Russian tanks rolled across the border into Ukraine. But he’s also granted humanitarian, visa-free admission to any Ukrainian who shows up as a refugee. Above all, he’s assuring the nation that his position will keep Hungary out of any bloody war that might spill over Ukraine’s frontiers—certainly keep his nation’s troops from being dispatched to deal with a conflict in which they have little direct interest.

In many respects, it’s not unlike life under the last decades of communist rule in Hungary. In 1956 when Warsaw Pact forces rolled into Budapest to suppress the Hungarian Revolution, something special and truly unique happened that still resonates profoundly there today. The Kremlin installed a ruler, Janos Kadar, who pledged to keep Hungary loyally within the communist and non-democratic sphere while at the same time enabling a freedom and prosperity at home unlike any enjoyed in other east European nations.

When I was visiting Hungary, quite freely in the late 1970s as a New York Times correspondent, I had a close friend who was a Hungarian academic, somewhat of a free speaker and son-in-law of Hungary’s venerable poet laureate, Gyula Illyes. The whole Illyes family, including my friend, lived in a charming house just across the road from the home of Kadar himself. “He just likes to make sure he can keep a close eye on us,” my friend would joke. Not really a joke. Much like today, Hungarians had a unitary source of news and information, cradle-to-grave social safety nets and the ability to speak more or less freely. The trade-off: they had one unquestioned leader who delivered everything he promised.

Not all Hungarians, of course, believe in this today, just as not all Hungarians believed it back then. Many of Fidesz’s ubiquitous posters in Budapest pledging to “protect the peace and security of Hungary” have been spray painted with the letter “Z,” reminding voters of Orban’s close ties with the Kremlin. And few voters have failed to observe Orban’s inability to stem the plunge of the Hungarian currency, the forint, to record lows or hold in check the soaring inflation that hit a 15-year high of 8.3 percent in February.

Along the way, Orban has been able to make some very attractive promises. His plan is to keep cheap Russian gas flowing to Hungary while a new $12.5 billion joint venture nuclear power plant with Rosatom remain on track. At the same time, to avoid being swamped by a tide of anti-Russian, certainly anti-Putin sentiment in the wake of the brutal war in Ukraine, Orban has been struggling to re-make himself, painting Fidesz as the safe choice for Hungarians in a fraught world and an especially dangerous neighborhood.

While this will be the fourth time he has presented himself to the Hungarian people for their endorsement, Orban has not abdicated his position as very much a man of the people. His campaign stops, immortalized in stylized videos, have included a traditional pig killing in a rural village followed by a demonstration that he still knows how the peel off its skin followed by shots of brandy with the townsfolk.

Still, even if all of this fails, over his 12 years in office, Orban has managed to ensconce a political voting system that all but ensures he will win, absent an utter landslide for the opposition. Still, if all else fails, there’s always a recourse to outright fraud. Which has never failed Orban in the past.

David A. Andelman is a Special Contributor to Diplomacy in Ireland - European Diplomat. He is twice winner of the Deadline Club Award, is a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor, author of "A Red Line in the Sand: Diplomacy, Strategy, and the History of Wars That Might Still Happen" and the SubStack blog Andelman Unleashed. He formerly was a correspondent for The New York Times and CBS News in Europe and Asia. The views expressed in this commentary belong solely to the author. View more opinion on CNN.