by Miceál O’Hurley

Diplomatic Editor

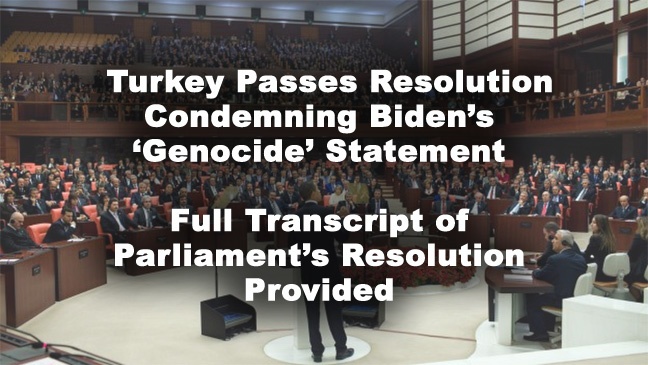

ANKARA — The Grand National Assembly of Turkey, its parliament, unanimously passed a resolution on 7 April 2021 condemning United States President Joe Biden’s 24 April 2021 Statement in which he referred to the deaths of 1.5 million ethnic Armenians between 1915-1917 as ‘genocide‘. Diplomat Ireland reported on this issue previously when Biden released his Statement on 24 April.

Biden fulfilled a campaign promise made during last year’s election campaign to declare the deaths of the Armenians during this period a ‘genocide’. Previous U.S. Presidents specifically refrained from using the term ‘genocide‘ when characterising the deaths of ethnic Armenians throughout Anatolia during World War I while it was under the authority of the Ottoman Empire. The Armenian diaspora has long campaigned to have the events recognised officially as ‘genocide’.

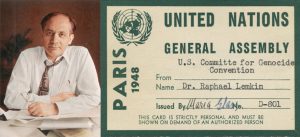

Biden’s use of the term ‘genocide’ comes at a particularly difficult period in U.S.-Turkey bilateral relations. The two NATO allies have a long-standing friendship which has been in decline for the past decade, increasingly so in the past few years. Moreover, Biden’s statement, while bolstering domestic political support from Armenian-Americans and many human rights activists, has been accompanied by not insignificant criticism by other human rights activists and legal scholars and academics who note that the term ‘genocide’ did not enter the lexicon until 1944. Raphael Lemkin, s Polish scholar of Jewish descent, coined the term in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The term came into being almost concurrently with the terms ‘war crime‘ and ‘crime against humanity‘ at the Nuremburg Trials. Many believe its application to prior historical events academically and ethically questionable.

Genocide as a Concept and Law

The term ‘genocide’ is a contrived linguistic device rooted in both the Greek and Latin languages, with genos (Greek for family, tribe, or race) and cide (Latin for killing), thereby constructing a new concept in linguistics, theory and eventually law.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 (A/RES/96-I). It represents the first human rights law established by the sorority of nations. Notably, genocide, as defined by the Convention, can arise either in peace or in war. According to the United Nations, it was codified as an independent crime in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention). The Convention has been ratified by 149 States (as of January 2018).

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has repeatedly stated that the Convention embodies principles that are part of general customary international law. This means that whether or not States have ratified the Genocide Convention, they are all bound as a matter of law by the principle that genocide is a crime prohibited under international law. The ICJ has also stated that the prohibition of genocide is a peremptory norm of international law (or ius cogens) and consequently, no derogation from it is allowed.

One of the difficult issues for modernity to grapple with is the issue of dolus specialis (special intent) when it comes to defining acts as genocide. A synopsis by the United Nations makes clear the exceptionally high bar applied in defining even the most dastardly of acts as genocide according to the Convention, “To constitute genocide, there must be a proven intent on the part of perpetrators to physically destroy a national, ethnical, racial or religious group. Cultural destruction does not suffice, nor does an intention to simply disperse a group.” It is this predicate existence and proof of dolus specialis that makes the crime of genocide almost unique in law. In addition, case law has developed that further requires such intent arising from the existence of a State, organizational plan or policy, even if the definition of genocide in international law does not include that element.

Application of ‘Genocide‘ to Historic Acts (Ukraine)

While some scholars and politicians reject the idea of applying the term genocide to historic events prior to the coinage of the word in 1944 by Limpkin, he himself chose to do exactly that during a 1953 speech given in New York City. During his remarks, Lemkin pointed to the Soviet Union’s execution of specific orders from Joseph Stalin that caused the death of millions Ukrainians when their agricultural production was forcibly exported to Russia, creating a planned famine that is known as the Holodomor. Holodomor, a Ukrainian word that translates as ‘killing by starvation’ (implying intent) is sometimes referred to in the West as the ‘Terror Famine’ which led to the death of over 13% of the Ukrainian population in a single year between 1932-1933 (A United Nations Joint Statement signed by 25 countries in 2003 declared that between 7 and 10 million Ukrainians perished).

Lemkin’s 1953 personal remarks on this topic, which occurred prior to his 1944 coinage of the term ‘genocide’, “… perhaps the classic example of Soviet genocide, its longest and broadest experiment in Russification—the destruction of the Ukrainian nation”, going on to point out that “the Ukrainian is not and never has been a Russian. His culture, his temperament, his language, his religion, are all different… to eliminate (Ukrainian) nationalism… the Ukrainian peasantry was sacrificed…a famine was necessary for the Soviet and so they got one to order… if the Soviet program succeeds completely, if the intelligentsia, the priest, and the peasant can be eliminated [then] Ukraine will be as dead as if every Ukrainian were killed, for it will have lost that part of it which has kept and developed its culture, its beliefs, its common ideas, which have guided it and given it a soul, which, in short, made it a nation… This is not simply a case of mass murder. It is a case of genocide, of the destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation.”

The Ukrainian Weekly contemporaneously reported on Lemkin’s New York speech, “An inspiring address was delivered at the rally by Prof. Raphael Lemkin, author of the United Nations Convention against Genocide, that is, deliberate mass murder of peoples by their oppressors. Prof. Lemkin reviewed in a moving fashion the fate of the millions of Ukrainians before and after 1932–33, who died victims to the Soviet Russian plan to exterminate as many of them as possible in order to break the heroic Ukrainian national resistance to Soviet Russian rule and occupation and to Communism.” Russia, the successor State to the Soviet Union, (as it takes pains to point out), denies the Holodomor constituted genocide, despite extensive records that establish a dolus specialis that supports its classification as a genocide visited upon the Ukrainian people and State.

Consequently, given Lemkin’s own application of ‘genocide’ to the Holodomor in Ukraine, many eminent scholars, as well as the Armenian diaspora, argue that the term ‘genocide‘ can, and should, legitimately be applied to the death of 1.5 million Armenians between 1915-1917. Turkey rejects this idea and has consistently argued they are confident the historical record, if properly examined, would prevail in vindicating the Ottoman Empire from the charge of ‘genocide’ . Turkey has offered to work within the context of a joint commission with Armenia to comprehensively study the matter. Since 2005, Turkey has offered not only to participate in a commission, but has offered to make their archives readily accessible to the world.

Accusations of Genocide Being Applied for Political, Not Legal Reasons

Biden’s statement brings the issue of the politicisation of genocide into sharp focus. For many, especially in Armenia, Turkey and the Armenian diaspora, Biden’s proclamation was long-overdue act of recognition of the incredible suffering experienced during WWI which left gaping holes in millions of Armenian’s ancestral trees resulting in the disappearance of entire families and communities. Many legal experts and human rights advocates, however, are not so quick to agree absent a credible historical tribunal that could make an exhaustive search of archives and contemporaneous documentation that might support the dolus specialis required to make a determination about ‘genocide’ according to international law.

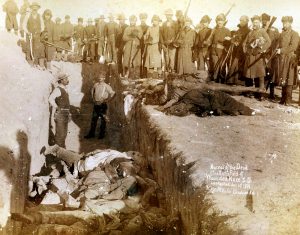

Moreover, as the Turkish Parliament’s Resolution asserts, there is a fundamental question of the ‘morality’ of Biden making such a proclamation given the United States’ own history. Such a historical record is replete with government documents, most notably the Indian Removal Act of 1830, arguably providing the basis for a determination of a dolus specialis with regards to Native Americans (sometimes known as American Indians). Even into the 20th century (during the same period as the deaths of the Armenians ocurred) Native Americans were systematically deprived of their lands, with a consequential loss of millions of lives. Others point to the United States’ not only historic, but ongoing issues relating to the enslavement, lynching or killing of Americans of Colour, specifically African-Americans, as a demonstration of Biden’s lacking of moral foundation to criticise Turkey. Turkey does not deny the deaths of the 1.5 million Armenians, but places them in the wider context of war, relocation, famine and a civil war which ethnic Turks and others in the Ottoman Empire also endured.

The question of the United States’ stance on morality and foreign policy arose recently in March 2021 during high-level meeting between United States Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Yang Jiechi, Director of China’s Central Foreign Affairs Office. During the first Sino-American meeting following Biden’s inauguration, Blinken pointedly accused China of undermining global stability with its treatment of China’s minority Uyghur Muslim community. Blinken has previously stated that the Uyghurs are being subjected to a ‘genocide’ by China. Blinken was equally critical of China’s policies and conduct in Hong Kong and its stance on Taiwan. Yang’s retort was that Blinken’s comments were not “normal”, referring to the United States’ lacking in moral and diplomatic superiority.

Scholars and politicians are increasingly grappling with the appropriate application of the emotionally charged term ‘genocide’ arguing its invocation supersedes a rational resort to the Convention’s definition and therefore lends itself to politicisation and propaganda. The record of human atrocities arising over the last century, from the deaths of the Armenians between 1915-1917 to the Holodomor, and from the Holocaust to the atrocities in Cambodia, Biafra, Angola, Uganda, Rwanda, Serbia or continuing events in Myanmar, Yemen, South Sudan, Iraq and Syria, or the Central African Republic are an indictment of the human propensity towards violence and the international community’s inability to thwart the mass killings of entire peoples, be it by ‘genocide’, war crimes or crimes against humanity, or simple murder, is lackluster.

A Path Forward

As for now, the continuing dispute over the application of ‘genocide‘ to the death of 1.5 million Armenians between 1915-1917 at the hands of the Ottoman Empire remains unresolved. Can it be resolved?

The case of Perinçek v. Switzerland, which was heard in the European Court of Human Rights, which issued its decision in 2013, only serves to highlight the difficulty of appropriately applying the term ‘genocide‘. Doğu Perinçek, an ultranationalist political activist and member of the Talat Pasha Committee, was convicted by a Swiss court for publicly denying the Armenian genocide. Perinçek claimed the conviction deprived him of his liberty to exercise free speech. The Grand Chamber ruled in favour of Perinçek. The decision not only invoked praise from legal scholars who pointed to the fundamental principle of freedom of speech, but was just as fervently criticised for running contrary to the historical record and being overtly anti-Armenian. Many Turkish nationalists point to the decision and claim it vindicates their position that the Armenian genocide did not occur, or that the legal definition of genocide could not be applied to a historical event. In short, even a seemingly clear decision by the European Court of Human Rights left both sides divided. All the while, Turkey continues to extend its now 15-year old offer to engage in a Joint Historical Commission to study the issue. The invitation has been continuously rejected by Armenia and the Armenian diaspora.

Today, the tit-for-tat exchanges that were wholly expected to issue as a result of Biden’s departure from the United States’ Presidents’ decades-long, traditional practice, of honouring the deaths and memory of the 1.5 million ethnic Armenians that died between 1915-1917, without specifically referring to the events as a ‘genocide‘, is causing new disputes. It has set-off a renewed debate between human rights campaigners and students of politics and international relations as well as creating a further rift in the already strained U.S.-Turkey bilateral relations. It has also caused the allies of each nation to be drawn into a the controversy. Nowhere is this more poignant than with Israel, a long-time ally of the United States, with strong regional ties to Turkey. The issue of ‘genocide’ is acutely ever-present in Jewish and Israeli life. Having to choose sides, or so carefully navigate this ‘razor’s edge’ between the United States and Turkey may cause even more difficulties that Biden imagined of was prepared to confront.

Turkey’s Parliamentary Resolution

Tuesday’s vote in the Grand National Assembly, Turkey’s unicameral legislature, approved the Resolution On Condemnation, Rejection, And Declaration As Null And Void Of The U.S. President Joe Biden’s Statement Of April 24, 2021, with it receiving the requisite signature of the Speaker of the Parliament, The Honourable Mustafa Sentop. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development (AK) Party, the Republican People’s (CHP) Party, the Good (IYI) Party, and the Nationalist Movement (MHP) Party all voted in favour of the Resolution. The Peoples’ Democratic (HDP) Party alone voted nay.

The Resolution, which strongly rejected and condemned the US president’s remarks, has been reproduced in English, below (it is also available here in Turkish, English, French, Arabic and Russian translations):

![]()

THE GRAND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF TURKEY

RESOLUTION

RESOLUTION ON CONDEMNATION, REJECTION, AND

DECLARATION AS NULL AND VOID OF THE U.S. PRESIDENT

JOE BIDEN’S STATEMENT OF APRIL 24, 2021

Resolution no. 1283 Date of Resolution: 27.04.2021

As the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, we deeply regret and vehemently condemn the U.S. President Joe Biden’s statement of April 24, 2021, in which he embraces the theses encapsulating the claims of Armenian lobbies regarding the events of 1915, and we reject, in the strongest manner possible, these unsubstantiated slanders, which serve no other purpose than distorting history with political motives. This statement by the U.S. President, who has neither the legal nor the moral authority to pass judgment on historical issues is null and void in our regard.

The reason for this irresponsible statement to be made 106 years after the events which took place in World War I conditions and brought about tragic results for both the Turkish and Armenian peoples of the Ottoman State is not that historical documents or international legal norms have changed but rather the fact that the U.S. Administration, immersed in small calculations of self-interest, has succumbed to the pressure coming from radical Armenian lobbies. Divorced from historical reality, this statement is an unwise and irresponsible step that does not contribute at all to the rapprochement between the peoples.

Turkey has argued that independent experts and historians should research the events of 1915, proposed in 2005 the establishment of a Joint Historical Commission to this end, and has made its archives accessible to the whole world. Turkey’s attitude which is frank, confident of itself and its history, open to cooperation and desiring for the scientific truth to be unearthed is rooted in its solid knowledge pertaining to the development and consequences of the events of 1915, and in its self-confidence about the fact that Turkey has never engage in hostility, either in its distant or near past, against a people as a whole. Therefore, no politician or government can have anything to reproach Turkey for, as it has never shied away from historical research and, on the contrary, supports any and all individual or joint research efforts related to the events of 1915.

“Genocide” is a concept in international law with a well-defined scope whose usage is dependent on very concrete conditions. Materialisation of this concept referring to a well-defined act of crime, as state in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, can only be adjudicated by a competent tribunal. None of the conditions necessary for the legal recognition of the 1915 events as genocide is in existence. Furthermore, the 2015 and 2017 judgments of the European Court of Human Rights set out very clearly that it is not possible to assign to the events of 1915 any further meaning than a historical debate. Beside, it is a great legal and moral irresponsibility on the part of a politician, whatever their title or office might be, to attempt to pass judgment on an issue which clearly falls under the authority of tribunals.

It is apparent that President Biden’s statement about the events of 1915 will only serve to polarise the two peoples, bolster the agenda of radical and extremist groups, and encourage hate speech, whereas sincere efforts must be made to ensure lasting and sustainable peace in our region and to enable the peoples of the region to live in prosperity and security.

In this context, we invite President Biden to alter his mistaken statement, which is far from historical reality and which has profoundly wounded the conscience of our people, to support the efforts towards ensuring peace, stability, and security for the peoples of the region, primarily the Turkish and Armenian peoples, and to reverse his decision, which is bound to have negative impacts on our bilateral relations.

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey, whose 101st anniversary of inauguration we proudly observe, will, with unwavering resolve and determination, continue to defy and unjust statements or acts against our august nation and country and will always stand by our national pride, independence, and history, every period of which we take pride in.

This resolution on the condemnation, rejection, and declaration as null and void of the U.S. President Joe Biden’s statement of April 24, 2021 was voted for and adopted in the 78th Session of April 27, 2021 of the General Assembly, with the resolution to be published in the Official Gazette.

#####