by Miceál O’Hurley

TORONTO — Following mass public protests, including from Members of the Canadian Parliament, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) has cancelled scheduled screening of the Russian-Canadian film, Russians at War. The film, jointly funded by Canadian ministries and bodies along with their French counterparts is the work of Anastasia Trifomova who wrote, directed and stars in the film which she claims is an “anti-war” documentary. Critics have highlighted how the film portrays Russian invaders of Ukraine as “victims” of war, seeking to absolve even Russian volunteers of personal responsibility for their role in a war that has caused more than 500,000 casualties. Russia’s increasing tactic of targeting civilians, housing, hospitals, cultural centres and schools have marked the war as particularly brutal. Independent international investigators have documented and verified the rape of civilians (including children and the elderly), the kidnapping of children, torture, summary execution and acts that meet the definition of genocide in all territories in which Russian forces operate and occupy.

Last week, TIFF issued a statement that they would suspend screenings of the film for security reasons:

Effectively immediately, TIFF is forced to pause the upcoming screenings of Russians at War on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday as we have been made aware of significant threats to festival operations and public safety. While we stand firm on our statement shared yesterday, this decision has been made in order to ensure the safety of all festival guests, staff, and volunteers.

TIFF resumed screening the film 2-days ago. There have been no known reports of security breaches or threats to TIFF operations made to the Toronto Police Service since the festival re-commenced screening the film.

TIFF’s decision to pause screenings of Russians at War citing claims of “significant threats” were at odds with information provided by the Toronto Police Service. According to TIFF CEO, Cameron Bailey, “In emails and phone calls, TIFF staff received hundreds of instances of verbal abuse. Our staff also received threats of violence, including threats of sexual violence. We were horrified, and our staff members were understandably frightened”.

A spokesperson for the Toronto Police Service told Canada’s Global News the decision to suspend the screenings were made by TIFF organizers “and was not based on any recommendation from Toronto Police,” who are not aware of any active threats. “We were aware of the potential for protests and had planned to have officers present to ensure public safety,” the spokesperson said. TIFF invocation of threats to festival operations and public safety have proven hyperbolic and seem centred on concern over what transpired to be orderly civic protests. TIFF organisers have been roundly criticised with many claiming the reasoning for the suspension of screenings of what protesters deem a propaganda film was itself part of a lingering trend of apologist that benefits Russia and maligns critics.

The Russian-Canadian filmmaker Anastasia Trifomova has denied her film constitutes Russian propaganda, claiming vicariously that she is neither part of the Russian propaganda apparatus nor that she produced the film with Russian permission. Trifomova’s background includes having produced a documentary for the universally recognised Russian propaganda outlet RT (Rossiya Segodnya) raises significant concern about her credibility. RT was banned this week by the social media giant META for “foreign interference activity“. Other statements by Trifomova undermine her claims of editorial independence and not having been given permission by Russia to produce her film.

In the end, I reached the highest brigade commander... I repeated the same words - about the Great Patriotic War, about journalists and about Berlin... And he ordered that I be given a military uniform - "so that my own people don't accidentally shoot me."

Trifomova has claimed publicly she met a man she called “Ilya” on a train in December 2022. He helped her gain access to the frontlines and once there, she was given the approval of the military commander for filming and he provided her with a uniform, food, housing and security. It is paradoxical that Trifomova claims she made the film without permission but recounts the military commander having consented to her work and remarkably, without the right of review or censorship. It is possible that it was understood her work would be of value to the Russian propaganda machine.

In an interview published on 5 September by the Russian publication People of Baikal, Trifomova revealed a startling detail that has been virtually missed in the hailstorm of media surrounding what has been widely described as a work of propaganda that seeks to humanise Russia invaders of Ukraine as “victims”. Trifomova’s attempts to defend her work as independent of Russian editorial control are countered by her own responses to questions in the People of Baikal interview.

Trifomova is quick to deny she had “official” Russian permission to be present with Russian soldiers as a documentarian. The claim is disingenuous. Her statement that she began to seek permission from a Platoon Commander up to the Brigade Commander would have required for her to seek permission from no less than 4-different officers, a Platoon Commander, Company Commander, Battalion Commander and then the Brigade Commander. While there is no proof Trifomova received sanction for her work from Moscow in being embedded with a Russian combat unit for what she claims was over 7-months there can be no question that permission was granted by the Russian military. It is unlikely, given the manner in which command is exercised in the Russian military, that the permission granted to Trifomova by the Brigade Commander wasn’t granted by higher authorities in Moscow, though she does not state as much.

In gaining permission to make her film from the Brigade Commander it is reasonable to assume that Trifomova would have had to explain her experience. Citing her employment with RT would have proved persuasive in validating her adherence to the propaganda of the Russkiy Mir.

A more fundamental question arises concerning her ethical and moral responsibility as a documentarian in asking the questions that go to the heart of the conflict. Had Trifomova tried to elicit answers to the natural questions that other journalists and documentarians are asking she would have quickly been removed from the unit and given other examples of attempts at independent reporting and been sent to Moscow for prosecution. Given there is no indication that Moscow is even contemplating charging Trifomova for violating Russia’s law against spreading “false news” about the war it reinforces the idea that the work has met with Russia’s approval.

In June 2024, Moscow issued arrest warrants for Russian independent journalists Farida Kurbangaleyeva, Ekaterina Fomina and Roman Anin for spreading “false views” about the Russian military. The 3-journalists represent only a fraction of the repression of truthful reporting from or about Russia. In March 2024, Roman Ivanov, a reporter for RussNews, was sentenced to 7-years in prison for being critical of the decision by Russia to invade Ukraine and report truthfully about the misconduct of the Russian military in prosecuting the war. Sergei Mikhailov, a Russian journalist, was arrested in 2022 then sentenced to 8-years in prison for “intentionally spreading false information” about the Russian army for reporting on the murder of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha and Irpin by Russian forces. In another of many such cases, Andrei Novashov was remanded for 8-months of “corrective work: after having been accused of distributing “fake news” about Russian armed forces and was prohibited from engaging in journalistic activities for a year.

That Trifomova has not been indicted and made subject to arrest by Moscow for what she claims is an “anti-war” film demonstrates that it is anything but an anti-war film. Russians at War and Trifomova herself have escaped scrutiny specifically because it does not seek to document the reality of Russia’s war in Ukraine, including documenting the ongoing war crimes, but specifically because it is co-aligned with the goals and objectives of Russia and its military.

The following is a verbatim excerpt from the People of Baikal interview with Trifomova:

— I thought that when I got there, they would immediately arrest me or just send me back. I got to the village where the battalion was stationed, this is the territory of the self-proclaimed Lugansk People's Republic. 180 kilometers to the front. I found Ilya, met his comrades. I said that I was making a documentary, that now in our country the main event in modern history is this war, and you are its main participants. And that I would like, if you don't mind, to film you. To my surprise, everyone said - why not, just talk to our platoon commander. And the commander said - why not, talk to our next commander. He said that he liked my proposal, because it reminded me of the Great Patriotic War - then journalists with military units reached Berlin. I thought - yeah. In the end, I reached the highest brigade commander. I repeated the same words - about the Great Patriotic War, about journalists and about Berlin. He looked at me and said - you're kind of strange, why do you need it at all. I said - well, why, the main event. He told me - well, I don't know, let me think about it, you sit quietly for now and don't show yourself at all. He didn't exactly allow it, but he didn't forbid it either. And he ordered that I be given a military uniform - "so that my own people don't accidentally shoot me."

Despite Trifomova’s claims she did not have “official” permission for her film she readily admits she sought permission from the military chain of command and received it. Contrary to her several claims that her work was a “anti-war” film, it is clear the Russian military commanders saw it much differently, likening it to the work of Russian journalists in the ‘Great Patriotic War’ (World War II) in Berlin. It is universally accepted that many of the more recognisable battle scenes filmed by Russian “journalists” in the battle for Berlin were the product of stagecraft and often, re-enactment. The iconic image captured by Soviet war photographer Yevgeny Khaldei, as published on 13 May 1945 in the Ogonyk magazine, was itself a stage-managed re-enactment.

According to Trifomova’s account, military commanders approved her presence and work specifically because it was for propaganda purposes. Trifomova’s claim that she did not receive “official” permission but recounting how she gained permission from the military chain of command is simply misdirection. Whether the permission came from military commanders in Moscow or the military commanders in the field, permission was sought by her and it was granted. It is without dispute that Trifomova was a cooperator with the Russian military and present with their tacit permission which included ordering her to wear a Russian military uniform.

It is Trifomova’s willingness to wear the military uniform that raises the most glaring inconsistencies with her story and attempts to reconcile reality with her revisionist account that she is not a propagandist. Journalist enjoy the protections of international humanitarian law. Except for serving military reporters, independent or agency journalists and documentarians have long dispensed with wearing military uniforms so as not to be confused with military personnel as they once did in World War II, Korea and at times in Vietnam. War correspondents come under the ill-defined category of “persons who accompany the armed forces without actually being members thereof”. It is difficult to understand how Trifomova maintains she was independent as she wore the uniform of the Russian military in the performance of her work.

It is the last line in the excerpt which is most chilling, however, and challenges her assertion that she did not witness any war crimes. Trifomova recounts, “…he ordered that I be given a military uniform – “so that my own people don’t accidentally shoot me”. In what she portrays as a reasonable explanation for why she wore a uniform contrary to journalistic and documentarian standards in a war zone Trifomova betrays a dark truth – Russian soldiers target civilians. The Armed Forces of Ukraine wear standardised uniforms and depending on the day, often wear tape markings to help distinguish themselves as Ukrainian soldiers.

The only reason a military commander would order Trifomova to dispense with her civilian clothes and wear a Russian military uniform arises from the reality that an inordinate amount of Ukrainian civilians have been summarily shot or executed by Russian soldiers since the invasion of Donbas began in 2014. Her statement to People of Baikal indicates the threat to her safety did not arise from the Ukrainian military while Trifomova while dressed in civilian clothing – the fear was that Russian forces would shoot her if dressed like a civilian. What more telling admission could there be that the killing of civilians was part of the Russian military culture such that only by wearing a Russian uniform could her safety be guaranteed?

The growing realisation that Trifomova’s Russians at War and the outrage that it has generated by being screened by heralded film festivals has led to sharp condemnation. Initially, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) released a statement defending Trifomova and her film:

Our understanding is that it was made without the knowledge or participation of any Russian government agencies. In our view, in no way should this film be considered Russian propaganda.

TIFF’s statement runs contrary to Trifomova’s interview with the People of Baikal. The assertion that “it was made without the knowledge or participation of any Russian government agencies” is belied by Trifomova admitting she received permission from the Russian military command operating in Ukraine. TIFF’s attempt to claim a difference between the Russian military command and any Russian government agency is a distinction without a difference. Trifomova could not have made the film without the permission of Russian military commanders in the field and conforming to their stated expectations that it would be a propaganda piece.

Trifomova admits herself to agreeing to produce a work of Russian propaganda, “I reached the highest brigade commander. I repeated the same words – about the Great Patriotic War, about journalists and about Berlin”. Russians at War is no “anti-war” film as she claims and including interviews with Russian soldiers asserting themes such as “Russia and Ukraine have always been inseparable” and displaying an image of Vladimir Lenin with the Russian soldier narrating, “I miss the camaraderie” are clearly propagandist themes even harkening to returning Ukraine to subjugation under the Soviet Union.

TIFF’s delusional Russian apologetics about the film Russians at War, “In our view, in no way should this film be considered Russian propaganda” rings remarkably akin to Nazi apologists claiming Lenni Reifenstahl’s films weren’t propaganda but rather “artistically beautiful cinematic masterpieces”. Whatever artistic value TIFF may believe Russians at War has, and little is discernable, their attempt to pass the film off as an authentic documentary which accurately captures the subjects, place and time instead of the propaganda piece that it is speaks to a larger void of ethics and moral integrity.

Last evening, Tiff released a statement which announced, “Effectively immediately, TIFF is forced to pause the upcoming screenings of Russians at War on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday as we have been made aware of significant threats to festival operations and public safety”.

In the final analysis, TIFF has managed to give weight to a quote by “Art is a lie that makes us realise truth”. The truth exposed by Trifomova, Russians at War and the willingness of film festival organisers to give a platform to propaganda and deceptive filmmakers who engage in deception in the production of their works which they attempt to pass-off as “anti-war” art is that the willingness of the world to close their eyes to the ongoing catalogue of war crimes and human rights abuses by embracing propaganda as art shows a disturbing willingness for some to fight for what they believe is the artistic freedom of filmmakers and yet ignore the violations of freedom of human beings who have suffered year-in and year-out for over a decade at the hands of Russian invaders.

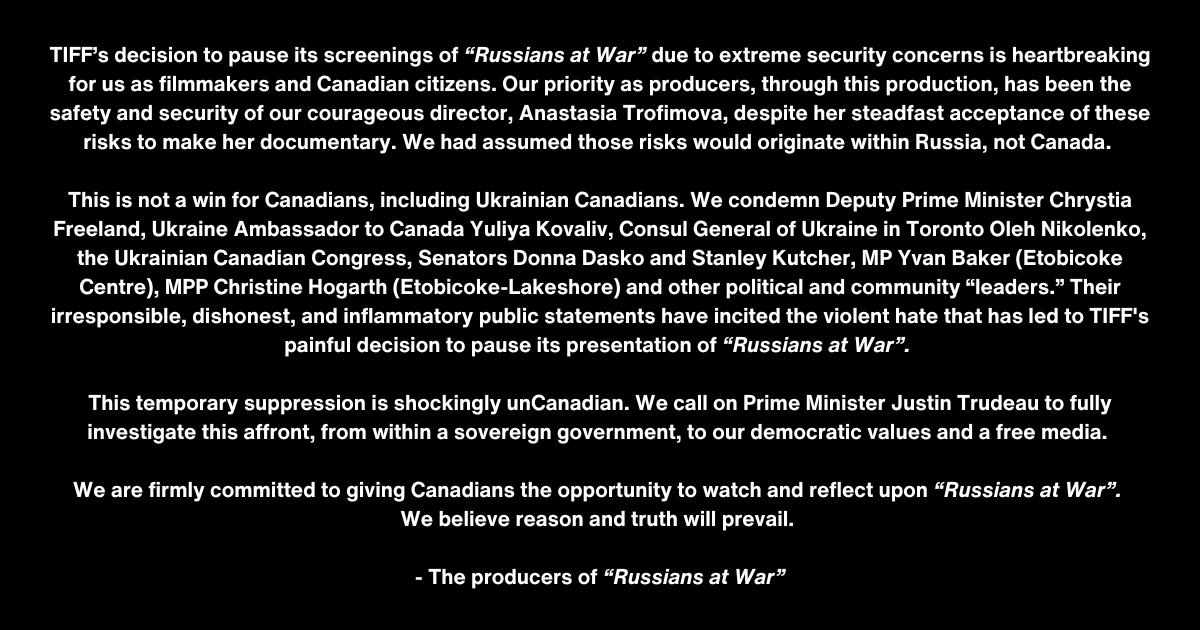

Last week, Trifomova and the other producers of Russians at War released a statement condemning the cessation of the screening of her film and decrying, “We believe reason and truth will prevail”.

There is little “truth” to prevail in a film produced to exonerate Russian invaders of Ukraine, made with the permission of the military commanders in the field, and a work that has escaped any censorship by the Kremlin while authentic reporters and film makers like Farida Kurbangaleyeva, Ekaterina Fomina and Roman Anin are subject to arrest for spreading “false news” about the Russian military and its operations in Ukraine. That Trifomova claims to have managed to have not documented any misconduct or war criminality by the Russian soldiers with whom she was embedded runs contrary to journalists who almost daily document and report news which correspond to internationally documented war crimes, crimes against humanity and assessments of genocide. Trifomova’s film leaves little room but to accept that it was a work created in the Russian interests and approved by the highest levels of the Russian government whether they actually issued “permission” or not.

That Trifomova’s film manages to portray Russian invaders, including volunteers, as innocent victims of war while managing to avoid documenting the war crimes that have featured so abundantly in Russia’s conduct of the war renders her film little more than propaganda. The decision by film makers to screening a film that seeks to absolve the soldiers who carry-out an invasion of a neighbouring country in service to the cause of Russkiy Mir is a shameful act. Being on the wrong side of history may be the TIFF organisers’ most lasting impression on the public and the annals of history.