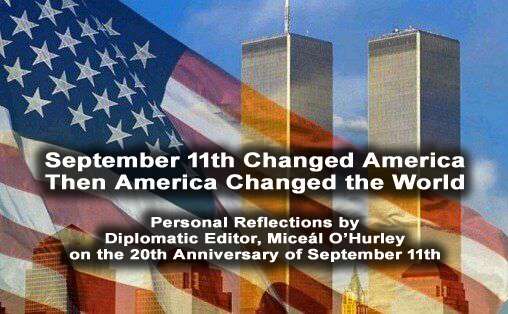

by Miceál O’Hurley

New York – It was a crystal blue autumn day in New York. Traffic jammed the Holland Tunnel, the George Washington Bridge carried throngs of commuters into the city and the Staten Island Ferry discharged those who worked in lower Manhattan, many in the Port Authority’s two, stunning World Trade Centre towers. As the commute came to an end the nightmare of September 11th and two decades of pain, suffering and disarray on the world stage would begin.

Those two aircraft that were steered into the ‘twin towers’ changed everything for America. America then changed everything for the world.

I took it personally. This was my old neighbourhood. The people who worked in the towers, and many who died on September 11th were my friends. The Irish-American Firefighters at Ladder 20, many of whom were my fellow members in the Ancient Order of Hibernians and attended morning Mass at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral with me were like brothers. I also lost friends in the Pentagon and one on United Airlines Flight 93. In the days and months following that horrendous day there were funerals and memorials for 27 of my friends. Despite being hardened by combat as a young man in uniform, the pain and losses of September 11th stays with me like an indelible stain on a much loved article of clothing.

That day I was immediately called into the studio at CTV News in Toronto to give my ‘expert’ commentary and perspective. I had no idea that I would return to that chair, time-and-again, over the next few years as the United States irrevocably committed itself to its policy of waging a ‘War on Terror’. As if from an extract from Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, America’s Caesar’s would ensure that a generation of citizens would never know a life without war.

Only three scant days after September 11th, the United States Congress, which includes the Senate (once described as the greatest deliberative body in the world) passed an unprecedented Authorisation for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) that gave then President George W. Bush almost the carte blanche authority of a Roman Emperor to wage war anywhere and everywhere he thought appropriate:

Only three scant days after September 11th, the United States Congress, which includes the Senate (once described as the greatest deliberative body in the world) passed an unprecedented Authorisation for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) that gave then President George W. Bush almost the carte blanche authority of a Roman Emperor to wage war anywhere and everywhere he thought appropriate:

That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

By this Resolution, the United States’ Congress arguably abandoned its legislative oversight to the Executive branch – the same branch of government empowered by the Constitution to wage war. Congress compounded their error, repeatedly, by reflexively authorising each successive request for billions of dollars for twenty years of combat operations (both overt and covert), against ‘enemies foreign and domestic.’ The consequences of Congress’ abdication of its responsibilities are still felt acutely in America and abroad.

There was one, sole dissenter in the House of Representatives that day. Congresswoman Barbara Lee, a woman of colour serving in only her second term in office. She bodly took to the well of the House of Representatives and spoke ‘truth to power’ with a bravery and prescient insight no others could find in their souls or intellect that day. The fear of elected Members of Congress looking weak in the immediacy following the attack on American soil outweighed their obligation to be wise for the longevity of the American experience. Lee warned her colleagues that the AUMF resolution would be exercised as “… a blank check to the President to attack anyone involved in the Sept. 11 events — anywhere, in any country, without regard to our nation’s long-term foreign policy, economic and national security interests, and without time limit.”

And here the power of language is instructive. In a mere sixty words, the checks-and-balances of American politics vanished with the result that more than 63 military operations in 14 countries were deemed to have been authorised (and countless more covert operations in countries of which the world may never learn). Like the Gulf of Tonkin resolution passed by Congress in 1964 which expanded America’s military involvement in Vietnam to a full scale war, the post September 11th AUMF resolution would do the same, proving Hegel’s axiom, “The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing.”

Without disservice to the dead, there is little need to recount the human losses, destruction of property, fall of nations or recall the dismembered women, children, men, elderly, orphaned, dispossessed, maimed or disturbed souls that were the results of September 11th or the two decades that have passed. Both their memory and their presence remain with us as a haunting reminder of misguided foreign policy and the folly of unrestrained war.

Those who planned the attacks on that sad day are as guilty as those who carried them out. It was a savage, indiscriminate attack. For the many who cheered the destruction and death of September 11th, they share the burden of having urged on the violence. In planning a terrorist operation specifically designed to be so deadly and insulting, then have some celebrate the carnage, only one thing was bound to result – a more lethal and enduring cycle of death and destruction. This is too often the goal of terrorists.

The dead of September 11th deserved justice, not revenge. They have been given neither.

The dead of September 11th deserved justice, not revenge. They have been given neither.

The elimination of Osama bin Laden and the varying degrees of degrading terror networks around the world did not bring back the dead, rebuild towers, restore the lives of countless civilians or maintain world order and the rule of law. Nor has the ‘War on Terror’ made the world a safer place. It was a failed idea of inception to implementation with scant notice of evaluation. There must be a better way.

Diplomats are more than aware of the power of their words. Speeches are painstakingly written and re-written and assessed by various departments to ensure they deliver the appropriate message in the hope that clarity will avoid unintended consequences. Those who serve in the foreign service, providing advocacy and information to foreign partners (and at times competitors and opponents), and engaging domestically with legislators and executives of government, are judicious in their language, even their physical posture and dress. These are the soft instruments of Statecraft – the interpersonal skills and presentation of those who engage in diplomacy in the service of their country.

Standing in the shadow of the past two decades of pain, suffering and disarray on the world stage, it is the very power of words that should be the enduring lesson we carry. A mere sixty words, uttered and recorded within only 72 hours of a horrific attack, on largely civilian targets, without the full clarity of whom the bad actors were or the networks upon which they relied, irreparably changed our world. Sixty words.

It is with dismay that Americans, of all peoples, should have hurried with such abandon given the United States’ reliance on language in its guiding and sustaining foundations. Thomas Jefferson knew the power of language when he wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and then authored the Virginia Statue for Religious Freedom a decade later. Both remain poetic and enduringly powerful in their clarity, brevity and device. Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison understood the power of language when they crafted the Federalist Papers between 1787-1789, arguing their views during the long deliberations of America’s Constitutional Convention. Abraham Lincoln understood the power of words when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing America’s slaves in the midst of a civil war and then honoured the dead in his Gettysburg Address. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s uttering of “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” during the Great Depression began to transform a nation with the imagery of hope. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” moved Americans to reflect and act on social and racial injustice. And, Neil Armstrong’s words when first stepping onto the virgin surface of the Moon, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” still endures as a testament to humanity’s commonality, even if with imperfect unity. It is time for America to reflect and refocus on that which informs the present.

The common element in each of these examples is that all those words were chosen with equanimity and uttered in the cause of calling us to a higher purpose. The American Congress forgot that lesson in the days following September 11th, with one exception, Barbara Lee. Her courage needs to be remembered as a guiding example on this most retrospective of days.

In the final analysis on my personal reflections on this twentieth anniversary of September 11th, I recognise that despite the passage of time, I continue to carry with me the memory of those whom I loved and lost on September 11th and thereafter as deeply as I do my own pains and the scars of the war which I incurred as a young soldier on the battlefield, and as deeply I my memories of the killing fields around the world from which I reported over the decades as a journalist. This is the burden of being involved with humanity at both its worst and its best. Albeit, I remain a creature of hope. I remain convinced it is within the human experience to learn, to progress, to wage peace with the same passion when required to wage just war and to forge a better world.

It is now for diplomats to make the world fit for humanity, heal the wounds we now carry and limit those yet incurred. If sixty words changed the world for the worse, diplomats must find others, equally as powerful, fundamentally more persuasive, and ultimately more prevailing in the cause of peace and the service of humankind. Be it sixty or six thousand, those words must prevail.

It is now for diplomats to make the world fit for humanity, heal the wounds we now carry and limit those yet incurred. If sixty words changed the world for the worse, diplomats must find others, equally as powerful, fundamentally more persuasive, and ultimately more prevailing in the cause of peace and the service of humankind. Be it sixty or six thousand, those words must prevail.

We that survive the horrors of the world carry a solemn obligation to the dead and suffering to make our world better. Only this will comfort those who now are remanded to the cold slumber of the Earth and the families and loved ones they left behind. After twenty years, this is the indelible and enduring truth that remains along with my fervent belief that diplomats and good will are the key to achieving that dream.